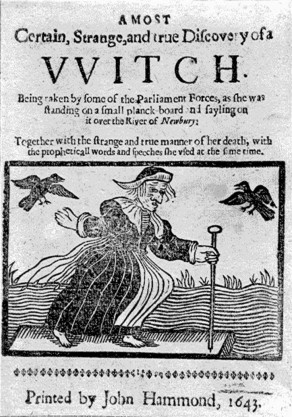

The separation of Church and state is seen as a pillar of modern society, but this was not always the case. For much of our history, the influence of the Church upon the general populace was matched only by its influence upon the laws of the state. This, in itself, was not an issue at the time as the views espoused by the clergy were widely held by lawmakers and thinkers alike. In 17th century Europe, many intellectuals and academics believed that the occult operated in tandem with the sciences and that the two were not mut ually exclusive. This group of enlightenment intellectuals included John Locke and Isaac Newton among their number. Influenced by both the laws of the time and the religious doctrine of the Church, such beliefs were widespread and culminated in the witch trials that swept through Europe and the Americas. The matter was complicated by the fact that the heresy laws were all encompassing, witchcraft simply constituted one of the many violations that fell under the general law of heresy. Framed as such, one bore the onus of proving that one was innocent of witchcraft and any other charges brought against their person. The reverse onus made it incredibly difficult for one to prove their innocence as the burden of proo

ually exclusive. This group of enlightenment intellectuals included John Locke and Isaac Newton among their number. Influenced by both the laws of the time and the religious doctrine of the Church, such beliefs were widespread and culminated in the witch trials that swept through Europe and the Americas. The matter was complicated by the fact that the heresy laws were all encompassing, witchcraft simply constituted one of the many violations that fell under the general law of heresy. Framed as such, one bore the onus of proving that one was innocent of witchcraft and any other charges brought against their person. The reverse onus made it incredibly difficult for one to prove their innocence as the burden of proo

f fell upon themselves rather than upon their accusers.

In England, the war against witchcraft finally ended with the adoption of the Witchcraft Act of 1735. This was a result, in part, of growing uncertainty among the public intellectuals. It was no longer the view that the sciences and occult could operate in parallel or that they shared any common thread. It was claimed that the practice of witchcraft and the influencing of the material world with esoteric forces (alchemy and the like falling under this bracket) was impossible and any to claim the ability to do so were charlatans. As this thought filtered down to the general populace, the legislators once again took steps to legislate against witchcraft. This time, however, with a different goal in mind. The Witchcraft Act made it a crime for any person to claim that another had magical powers or was practicing witchcraft. The maximum sentence for such a crime was one year imprisonment. Although this period saw a decisive change in the approach taken to religiously driven paranoia, the Church still had a great influence upon the boni mores of society.

Until 1961 it was, paradoxically, a crime to commit suicide. Those who attempted suicide and failed could be prosecuted and imprisoned. This law had been in force, in England and Wales, since 1554. The most obvious influence for this was the position the Church took upon the act. It was considered a mortal sin to com it suicide and the Church refused to bury the victim in consecrated ground.

it suicide and the Church refused to bury the victim in consecrated ground.

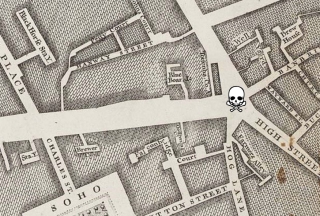

Indeed, up until 1823, the bodies of suicides were impaled with a stake and buried at crossroads. Medieval English judges had developed this method for two reasons:

- The burial of the corpse at a crossroads had symbolic meaning.

- Burial there made sure that the ghost of the deceased was kept firmly in place as a result of the constant passing of traffic. The ghost, supposedly becoming confused by the amount of traffic, would not know which direction to take.

There was, however, another rationale behind the approach taken by the English courts. In addition to the refusal to bury the body in consecrated ground, the goods and property of the deceased became forfeit to the state. Suicide was considered to be a crime against the monarch and, as such, a matter for royal justice.